13. Tuckman Model for Engineering Teams

If you’ve been around leadership training long enough, you’ve probably seen the classic team model:

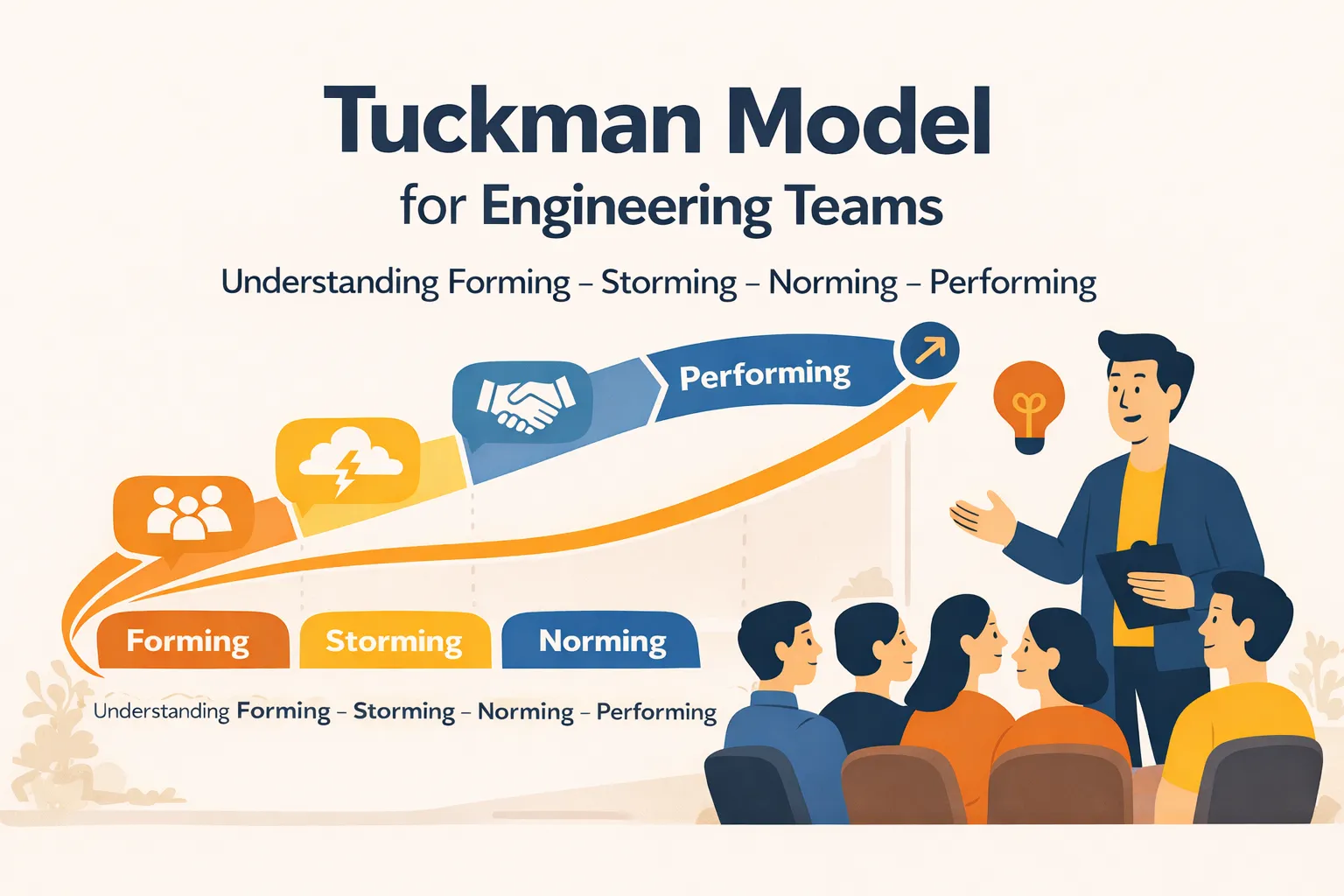

Forming – Storming – Norming – Performing (sometimes with an extra: Adjourning).

It’s easy to treat Tuckman’s model as something theoretical – a nice diagram on a slide.

But in real engineering teams, these stages are not abstract. You can feel them in meetings, code reviews, production incidents and planning sessions.

In this post I want to look at the Tuckman model from an engineering leadership point of view:

- What does each stage actually look like in a software team?

- What do good leaders do at each step?

- How does it connect with building trust, delegation, and team‑first organisation (see: Team and Project Organisation)?

My goal is simple: help you recognise your team’s current stage and intentionally lead it forward.

Quick overview: the Tuckman stages

The classic model:

- Forming – people are polite, cautious, still figuring out purpose and expectations.

- Storming – disagreements appear, frustrations surface, hidden tensions come out.

- Norming – the team starts to align on ways of working and shared standards.

- Performing – the team can deliver with high trust, autonomy and resilience.

Many models also add Adjourning – when a team ends or significantly changes.

Important: these are not checkboxes you tick once. Teams can move back and forth between stages, especially after reorgs, new joiners, or big changes in mission.

Your job as an engineering leader is not to “skip” stages, but to guide the team through them with as little unnecessary pain as possible.

Forming – setting foundations without over‑controlling

What it looks like

- New team created, or major re‑organisation.

- People are polite, a bit quiet, often more focused on looking competent than being open.

- Questions like: “What’s expected from me?” “Who decides what?” “Can I say what I really think?”

On the surface, Forming often feels “nice” – low conflict, everyone smiling.

Underneath, there is a lot of uncertainty and unspoken assumptions.

What you should do as a leader

In this stage you are a guide and architect:

- Introduce yourself properly. Share your values and how you work – not just your title. (More in: How New Engineering Managers Should Introduce Themselves).

- Clarify purpose. Why does this team exist? How does it connect to Product, Process, People (see: What Is Engineering Leadership?)?

- Set light structure. Standups, retro, planning – not as rituals, but as containers for conversation.

- Model vulnerability. Admit what you don’t know, ask for input, show it’s safe to speak.

The biggest trap here is to over‑engineer process too early. Don’t design a full operating manual in week one. Start simple and iterate with the team.

Storming – normal conflict, not a failure

What it looks like

At some point, reality hits:

- People disagree on architecture, priorities, or quality vs speed.

- Old habits from previous teams clash with new expectations.

- Side conversations start: “Why are we doing it this way?” “This meeting is useless.”

- You might see tension in code reviews or passive‑aggressive comments.

Many leaders secretly hope to avoid this stage. But Storming is normal.

Without it, you don’t discover misalignment or hidden expectations.

What you should do as a leader

Here, you are a facilitator and truth‑speaker:

- Name the stage. You can literally say: “We’re in the Storming phase – this is normal and healthy as long as we stay respectful.”

- Create space for real conversation. Use retros, 1:1s and small group sessions to surface what’s working and what’s not.

- Use structured feedback. Tools like the FUKO method (Facts, Feelings, Consequences, Expectations) help reduce defensiveness – see: Giving Feedback: The Power of the FUKO Method.

- Protect psychological safety. Challenge ideas, not people. Step in quickly against disrespect or blame.

Your job is not to eliminate conflict. It is to hold it in a constructive way until the team can integrate differences into better norms.

If you avoid Storming – by smoothing everything over, or deciding everything yourself – the team usually pays later in hidden resentment and low ownership.

Norming – turning agreements into habits

What it looks like

After a while, patterns start to stabilise:

- The team has clearer agreements: “This is how we handle incidents”, “This is how we do code review.”

- People know who to ask about what.

- Ceremonies have a clear purpose, not just calendar entries.

- Feedback flows more frequently, not just once a year.

You will feel less drama, more rhythm.

What you should do as a leader

Here you are a shaper and supporter:

- Document shared norms. Co‑create a simple Team Operating Manual: how we communicate, how we make decisions, how we handle outages. (This links well with First 90 Days as an Engineering Manager).

- Refine process, don’t explode it. Tweak standups, retros, and planning based on what the team says – not based on a textbook.

- Invest in growth. Use 1:1s for development, not just status. Delegation becomes a tool to build ownership – see: Effective Delegation Framework.

- Watch for quiet disengagement. Just because conflict is lower doesn’t mean everyone is energised. Check if people feel challenged and valued.

Norming is the perfect moment to start increasing autonomy – but gradually and with support.

Performing – autonomy with alignment

What it looks like

This is the phase every leader wants:

- The team delivers consistently, with good quality.

- People raise issues early, not at the last moment.

- Engineers drive initiatives themselves – you don’t need to be in every detail.

- Trust is visible: in code review, in incident response, in how people talk to each other.

There is still conflict and surprises (this is software, after all), but the team can handle them without falling apart.

What you should do as a leader

Here you are mostly a multiplier and strategist:

- Delegate outcomes, not tasks. Give the team ownership of problems (“Reduce time‑to‑restore incidents by 30%”), not just tickets.

- Remove external blockers. Fight for clarity, budget, or cross‑team alignment – things they cannot solve alone.

- Protect focus. Use prioritisation tools like the Eisenhower Matrix (see: The Truth About Prioritization in Engineering Leadership) to keep the team on what matters.

- Share visibility and credit. Let team members present to leadership, run demos, lead RFCs.

And very important: do not over‑intervene just because you feel bored.

When a team reaches Performing, some leaders unconsciously create new projects or changes to “add value”. Often they just reset the team unnecessarily. Instead, raise the bar by giving bolder ownership – not by adding chaos.

Adjourning – endings done with care

In tech we talk a lot about starting teams, much less about ending them.

Adjourning happens when:

- A team is split or merged in a reorg.

- The mission changes so much it’s effectively a new team.

- A project ends and the team is reassigned.

How you handle this phase strongly influences trust in leadership (see: The Biggest Challenges as an Engineering Leader).

As a leader:

- Acknowledge the ending. Celebrate what the team achieved. Don’t pretend nothing changed.

- Be honest about reasons. Share what you can – and clearly name what you cannot.

- Support people through the transition. Help them land in new roles or teams in a thoughtful way.

- Carry lessons forward. What did you learn about forming, storming, norming, performing this time?

Endings done well make it easier for people to commit fully next time. Endings done badly create cynicism that follows them into future teams.

Final thoughts

The Tuckman model is simple – and that’s its power.

It gives you a language to describe what your team is going through and to choose your leadership behaviour intentionally.

- In Forming, you give clarity and psychological safety.

- In Storming, you hold conflict and make truth safe.

- In Norming, you co‑create habits and invest in growth.

- In Performing, you multiply impact and protect focus.

- In Adjourning, you close the story with respect.

You can’t skip stages. But you can shorten the painful parts and strengthen the valuable ones.

If you look at your team today – which stage are you really in?

And what is one concrete action you can take this week to help them move one step closer to Performing?